Matrix major-ness in game engines

Published: 14-02-2026If you come form a formal math/theoretical background like me, you were probably taught that matrices are 2D arrays of arbitrary sizes and if you were to write a 4x4 matrix in C you'd probably just store 16 floats, maybe like this:

struct Mat44

{

float m00, m01, m02, m03;

float m10, m11, m12, m13;

float m20, m21, m22, m23;

float m30, m31, m32, m33;

};

In this post, I'll try to explain why such a general storage may not be always the best, how to chose between row or column-major matrices, and how to develop an intuition for these concepts by exploring the meaning of our matrices. For example, when the main purpose of our matrices is to store transforms we may want to do something like the following instead:

struct Vec4 { float x, y, z, w };

struct Mat44

{

Vec4 Right; // X

Vec4 Up; // Y

Vec4 Forward; // Z

Vec4 Translation;

};

This post is something I'd like to have read in the past when I was struggling with some of these concepts. There are no deep thoughts here, just very basic concepts explained through motivation and usage rather than theory. If this post confuses you more than it helps, I would suggest reading Fabian Geisen's post on the topic first.

I'm assuming a working knowledge of linear algebra and C (or a similar language). Since I'm not going very deep into any topic you should be able to easily lookup some of the terms I'm using with a quick Wikipedia search.

Motivation

Let's start with a question. How do we interpret the following 4x4 matrix in C?

struct Mat44

{

float m00, m01, m02, m03;

float m10, m11, m12, m13;

float m20, m21, m22, m23;

float m30, m31, m32, m33;

};

Based on the variable naming, it is stored in row-by-row (row-major) order in memory, but if we get a vector,

should we multiply it from the left or from the right by the matrix?

Since we can't tell if the vector is a row or column vector it does not really matter.

If we multiply with vector on the left v * M, we say that v is a row vector and M is a matrix of row vectors in row-major memory order.

If we multiply with vector on the right M * v, we say that v is a column vector and M is a matrix of column-vectors in row-major memory order.

Note that the devil is in the * operation. Since the matrix is stored the same way in memory (row by row), in one case we need to multiply the vector with each column and in the other we multiply it with each row.

At this point things look quite complicated already since we have two mathematical concepts (row vs column-vectors) and two memory storage options (row vs column major) which gives us 4 total combinations and which one we choose looks partially like a stylistic choice (multiply on left or right) and partially as a potential access pattern optimization.

I would say we approached the problem from the wrong end, though, and we should go back to the struct definitions and realize what we're storing in the matrix.

A side-note on matrix transforms

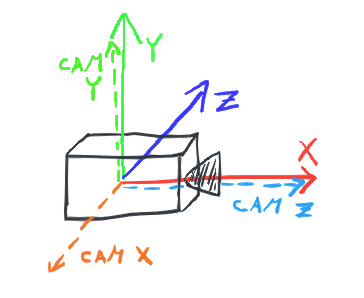

In this section we assume column vectors, the same would apply to row vectors, we would just have to transpose all the matrices and multiply from the other side. We also work in a left-handed space where X is right, Y is up, and Z is forward. This is also arbitrary but important.

To motivate our matrix storage needs let's take it the long way around and look at the main use-case of matrices in games which are transforms. Specifically, transforms between two coordinate spaces. A transformation matrix form space M to space W is created by interpreting the basis vectors of M in the space W and putting them as columns to a matrix. For example, if we have a canonical world coordinate system represented by three unit vectors

X: (1, 0, 0), Y: (0, 1, 0), Z: (0, 0, 1)

and a camera which looks to the right in the world (let's not worry about translations for now). The basis vectors of the camera in the world's coordinate space are

CamX: (0, 0, -1), CamY: (0, 1, 0), CamZ: (1, 0, 0)—we look in the direction of the X axis and the rest follows from that.

Putting the vectors as columns in a matrix:

( 0, 0, 1)

M = ( 0, 1, 0)

(-1, 0, 0)

So what is M good for anyway? Well, if we realize that in the camera's space the basis vectors of the camera are the canonical identity again (in camera's space, forward is positive Z of course), the matrix M transforms any vector from the camera space to the world space. We can informally prove it by transforming the basis vectors of the camera space. For example we would expect the right vector (1, 0, 0) to be transformed to the negative Z and that's exactly what happens if we carry out the multiplication.

( 0, 0, 1) (1) ( 0)

( 0, 1, 0) * (0) = ( 0)

(-1, 0, 0) (0) (-1)

That also makes perfect sense, though, since we defined the matrix M as "basis vectors of one space interpreted in another space". Multiplying a matrix by a vector (1, 0, 0) effectively pulls out the first column of the matrix.

So matrix M is actually M_camera_to_world. To get M_world_to_camera we could either do the same and represent world space in the camera space or just invert the matrix we already have (or just transpose it since it's orthonormal).

Another way to reason about this is to see vector/matrix multiplication as a linear combination of matrix columns where the vector elements are the linear weights instead of the common way of seeing multiplication as dot products between matrix rows and the vector.

v = (x, y, z); // xyz are scalars

M = (c0, c1, c2); // c012 are vectors

M * v = c0 * x + c1 * y + c2 * z;

If we see the vectors in the matrix as basis vectors of a space this makes perfect sense again. This is essentially how vectors can be defined–a (coordinate) vector v in space S is a linear combination of the basis vectors of space S. X coordinate of a vector is a measure of how far to go along the X axis of the space we're in etc. In case of the canonical unit space with basis vectors e0 = (1, 0, 0), e1 = (0, 1, 0), e2 = (0, 0, 1), every vector can be written as v = vx * e0 + vy * e1 + vz * e2 which is very boring but helpful for reasoning about things. The point is that just by transforming the basis vectors of a space, we transform all vectors of that space when written using the definition above. But that is exactly what we've done with our camera example. We rotated its basis vectors and conveniently put them into a matrix for an easy multiplication but we could also just write it long hand as mentioned here.

Back to major-ness

From the camera example, we see that if we use a matrix to store transforms, we can name our variables better than just m00 etc. One common way to name matrix variables is to store the vectors directly.

struct Mat44

{

Vec4 Right; // X

Vec4 Up; // Y

Vec4 Forward; // Z

Vec4 Translation;

};

// or more generally

struct Mat44

{

// These would be RowN in row vector world

Vec4 Col0;

Vec4 Col1;

Vec4 Col2;

Vec4 Col3;

};

Now, this makes much more sense. We know exactly what is stored in the matrix and how to interpret it. Of course a matrix may not be just a transform, so having a union over several representations internally is useful.

struct Mat44

{

union

{

struct

{

Vec4 Col0;

Vec4 Col1;

Vec4 Col2;

Vec4 Col3;

};

float m[16];

};

};

With this in mind we can revisit the original question of major-ness. The matrix above is a matrix of column vectors stored in column major order and vectors should be multiplied by it with the vector to the right v' = Multiply(M, v).

We can of course store the matrix of column vectors in row-major order. It would look like this.

struct Mat44

{

// i-th column is now stored in (xi, yi, zi, wi)

float x0, x1, x2, x3;

float y0, y1, y2, y3;

float z0, z1, z2, z3;

float w0, w1, w2, w3;

};

Just to be clear, the above could also be a matrix of row vectors in column-major order if we ignore the comment, which leads us to the next point.

Looking at both side by side, this may look familiar. In essence, the first is Array of Structs (AoS) storage whereas the second is Struct of Arrays (SoA). The memory has not changed of course, only the interpretation. Introducing this terminology into the mix makes things clearer in my opinion since it combines the two choices we made. Saying "column vectors with AoS matrices" for example or even just "AoS matrix" seems to say more than just "row/column major matrix". Or rather, "AoS matrix" says less but that is exactly the point. It speaks only about the memory ordering. Whereas "row-major matrix" to me always felt more "theoretical" and confusing, but maybe that's just me, if you understand the concepts either version should be fine. However, in case of a generic math library which would not specify row/column vectors, we cannot say AoS/SoA and row/column-major is all we have. And that's probably where the confusion lied for me—when theory meets practice and when I needed concrete instead of general.

ℹ️ Note on the multiplication functions and operator*. Sometimes libraries allow multiplication from both sides (they don't specify vectors as row/column as mentioned above). That is perfectly fine for a general purpose library where matrices are just a mathematical concept. But for game engines and custom math libraries this is IMHO quite unnecessary. There should be exactly one way to multiply matrices and it should contain either row or column vectors. We should pick one and stick to it throughout instead of relaxing the requirement. At worst, two people in the codebase will chose to interpret matrices two different ways and you'll have to do unnecessary transpositions in the end. What's pure evil though is when you choose one but there are still two functions to multiply - Multiply(M, v) and Multiply(v, M) where one flips the order of arguments internally. There is no excuse for doing this other than to confuse people reading the code.

What about SIMD?

Let's compare both AoS and SoA storage options on matrix-vector multiplication. Multiplying two 4x4 matrices does not really change, since we take rows of one of them and columns of the other. Changing memory storage only flips this.

In case of SoA, matrix-vector multiplication is just a series of dot products. Each row dot the vector.

Mul(M, v) = Vec4(Dot(M[0], v), Dot(M[1], v), Dot(M[2], v), Dot(M[3], v));

This is the school definition of multiplication. Assuming we store each vector (or matrix row) in a 128 bit wide CPU register (__m128 in SSE for example), the multiplication is a series of 4 multiplies followed by a horizontal add and a scatter/store. In SSE this is something like:

__m128 x = _mm_mul_ps(M.vec[0], v); // M[0].x * v.x, M[0].y * v.y, M[0].z * v.z, M[0].w * v.w

__m128 y = _mm_mul_ps(M.vec[1], v);

__m128 z = _mm_mul_ps(M.vec[2], v);

__m128 w = _mm_mul_ps(M.vec[3], v);

__m128 xy = _mm_hadd_ps(x, y); // (x[0] + x[1], x[2] + x[3], y[0] + y[1], y[2] + y[3])

__m128 zw = _mm_hadd_ps(z, w);

__m128 result = _mm_hadd_ps(xy, zw); // (xy[0] + xy[1], xy[2] + xy[3], zw[0] + zw[1], zw[2] + zw[3])

This looks nice, but keep in mind that the horizontal add (hadd) instruction tends to be much heavier than others such as multiply. Looking at the uops table suggests that (depending on the CPU) hadd may have 4x worse throughput and a bit worse latency as well. This may be important here since we have two independent hadd instructions and the last one which depends on their result.

How does this look like using AoS? At first sight, it seems to be way worse, since we don't have the matrix vectors conveniently stored in registers but remember that in the side note above where we described multiplication as a linear combination of the matrix vectors?

__m128 vx = _mm_shuffle_ps(v.v, v.v, 0b00000000); // x, x, x, x

__m128 vy = _mm_shuffle_ps(v.v, v.v, 0b01010101); // y, y, y, y

__m128 vz = _mm_shuffle_ps(v.v, v.v, 0b10101010); // z, z, z, z

__m128 vw = _mm_shuffle_ps(v.v, v.v, 0b11111111); // w, w, w, w

__m128 a = _mm_mul_ps(vx, M.vec[0]); // x * M[0].x + x * M[0].y + x * M[0].z + x * M[0].w

__m128 b = _mm_mul_ps(vy, M.vec[1]);

__m128 c = _mm_mul_ps(vz, M.vec[2]);

__m128 d = _mm_mul_ps(vw, M.vec[3]);

__m128 result = _mm_add_ps(_mm_add_ps(a, b), _mm_add_ps(c, d)); // a + b + c + d

That does not look half bad actually. We need to access parts of the register storing the vector and spread them to 4 other registers but after that the operations flow quite nicely. All the instructions have reasonable performance characteristics, we just have more of them (also the shuffle intrinsic performs moves and shuffles giving a bit more instructions still). However, for example on ARM NEON shuffles like this can be performed as a part of loading from memory making them essentially free.

So what conclusion can we make? Unless we measure on a specific architecture I would avoid any strong claims but at least neither storage looks like a straight loser. There are of course other considerations to be made. Is this our common use case? Do we mind over-alignment and storage overhead (Vec3 is 16 bytes)? Do we often access single vector elements? All of these are important but we should be able to analyze them in a similar regard.

What about shaders?

The last thing I want to briefly mention is how is matrix major-ness handled in shaders.

In HLSL we can choose matrix major-ness. This informs how are the matrices we upload to the GPU interpreted.

In HLSL we use mul to multiply matrix with a vector, it works both ways and can be used both ways in the same program

= HLSL trusts us to do the right thing. We can for example take a matrix full of column vectors and multiply it from the left by a vector in which case HLSL will treat it as row vector multiplied by a matrix of row vectors. All the more reason to be consistent.

MSDN HLSL docs

Conclusion

There are 4 combinations of matrix storage and interpretation. We have two options for vector interpretation - row or column vectors - and with that associated multiplication order - row vectors multiply matrices from the left, column vectors from the right.

| Row vectors | Column vectors | |

|---|---|---|

| Row storage | AoS | SoA |

| Column storage | SoA | AoS |

If you're new to these topics this could have been a lot to unpack but I hope I've left you less confused, not more, and hopefully you've gained some intuition for working with transforms in game engines.

References

- Fabian Geisen's blog: https://fgiesen.wordpress.com/2012/02/12/row-major-vs-column-major-row-vectors-vs-column-vectors/

- uops table: https://uops.info/table.html

- MSDN: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/direct3dhlsl/dx-graphics-hlsl-mul

Bonus: Deriving a "look-at" matrix

This is just a bonus tangent based on the section about basis matrix of a camera. It's not related to matrix major-ness but since we have all the tools and it's somewhat related let's talk about how to go about deriving a look-at matrix.

A "look-at" matrix is a view matrix which is usually conveniently constructed by providing two points in space. A point we look from and a point we look to. In cases where we look straight up or down we may also need the user to give us an "up vector". Given the explanation above, we should be able to easily construct such a matrix. All we need is the three coordinate axis of our view (camera) space - forward, right, and up, and its position. When we get these we can just arrange them in a matrix as we saw above.

The desired function signature would be Mat44 MakeLookAt(Vec3 from, Vec3 to), let's assume we never look straight up or down for now. The forward vector is just a normalized difference of the two vectors we get.

Vec3 forward = Normalize(Subtract(to, from));

Now, since our vectors should end up perpendicular to one another (and we assume never looking up or down) we can take (0, 1, 0) as an approximate up vector and using the cross product get a right vector. We need to make sure to normalize it because its length depends on the angle between forward and (0, 1, 0). Since we're in a left-handed coordinate space, the forward vector is the second argument in the cross product (remember that if you curl the fingers of your left hand through the first vector and then the second vector, your thumb points in the direction of the result).

Vec3 right = Normalize(Cross((Vec3){ 0, 1, 0 }, forward));

To get the real up vector we apply the same logic, it has to be perpendicular to both forward and right. These are already perpendicular and normalized so the result is a unit vector as well.

Vec3 up = Cross(forward, right);

Now we have our rotation. The translation vector has been given directly as an input from. Arranging these vectors as columns to a matrix gives us a "camera to world" matrix.

( right.x, up.x, forward.x, from.x )

M_camera_to_world = ( right.y, up.y, forward.y, from.y )

( right.z, up.z, forward.z, from.z )

( 0, 0, 0, 1 )

A "look-at" matrix is an inverse of this matrix since the common use-case is to transform points from the world space to the view (and projection) space. To invert this matrix we can exploit its properties and construction/functionality to avoid full blown general inversion algorithm. An example implementation of the whole function is given next. We also provide an additional approximateUp argument to remove the assumption of not looking straight up or down.

// approximateUp would be (0, 1, 0) in most cases

Mat44 MakeLookAt(Vec3 from, Vec3 to, Vec3 approximateUp)

{

Vec3 forward = Normalize(Subtract(to, from));

ASSERT((Abs(Dot(forward, approximateUp)) < 0.9999f),

"Given approximateUp vector is too close to the forward vector to make a lookat matrix this way"

);

Vec3 right = Normalize(Cross(approximateUp, forward));

Vec3 up = Cross(forward, right);

// Matrix transforms from world space to camera space. Therefore, we return

// the inverse of the camera matrix - negate the translation and multiply by

// transposition of the 3x3 rotation matrix.

// We first need to translate the vector to -pos and then rotate it, which

// would be done by two matrices, here we have the result of multiplication of

// those two matrices

Vec3 minusPos = { -from.x, -from.y, -from.z };

return (Mat44){

(Vec4){ right.x, up.x, forward.x, 0 },

(Vec4){ right.y, up.y, forward.y, 0 },

(Vec4){ right.z, up.z, forward.z, 0 },

(Vec4){ Dot(right, minusPos), Dot(up, minusPos), Dot(forward, minusPos), 1 }

};

}